The Second Amendment was born of tyranny.

This wasn’t a thought experiment or a debating trick. It was the kind of tyranny you could hear in boots on cobblestone.

It came from a king an ocean away who governed by delay and decree, sent soldiers where answers should have gone, and called obedience “order” when consent had already rotted. To the founding generation, King George III was not merely ineffective. He was the archetype of the Mad King: insulated, unaccountable, and increasingly reliant on force as consent evaporated.

The Declaration of Independence named the offense with surgical clarity, accusing the king of “rendering the military independent of and superior to the civil power.” By the time the Second Amendment was written down, that idea had already been argued, resisted, and paid for.

To the founders, the right to keep and bear arms was not a lifestyle or a slogan. It was civic infrastructure. A structural safeguard against the concentration of force in the hands of a ruler who no longer listened. Arms were never about posing or swagger. They were there to remind power that it answered to people who could, if pressed, answer back.

James Madison warned in Federalist No. 46 that standing armies detached from the people were the natural tools of oppression, insisting that “the ultimate authority… resides in the people alone.” Thomas Jefferson dispensed with euphemism altogether: “What country can preserve its liberties if their rulers are not warned from time to time that their people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms.”

The point was restraint, not revolt — a message sent upward to anyone tempted to rule by force once listening became inconvenient.

It began, famously, over tea.

A tax levied from afar. A Parliament unanswerable to the people paying it. Taxation without representation was not merely an economic grievance; it was proof that distance had replaced consent. The tea only mattered because it revealed how far away the decisions had drifted from the people living with them. What hardened into revolution was not the beverage itself, but the realization that power no longer listened.

Today, the wind moving across the land feels different. Sharper. Less symbolic. Less patient.

So whatever came of “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free?”

As Temporary Protected Status for Haitians and other immigrants in the Southernmost City expires, that question no longer feels rhetorical. It feels immediate. The promise etched at the feet of the Statue of Liberty was never meant as poetry alone. It was a declaration of national character — a rejection of distant cruelty and arbitrary power.

Remember the scar at her feet, the broken chains. Remember her daughters: generations who arrived under that lamp believing the republic meant what it said. After all she has witnessed, one wonders whether Lady Liberty herself would be tempted to slink home, lamp dimmed, exhausted by the distance between promise and practice.

In the late 18th century, militias were not mobs. They were regulated, local institutions. Participation was expected. Discipline was required. Responsibility was assumed. Bearing arms was civic duty, not grievance theater. You owned a musket because the republic might one day require you to stand watch — not against neighbors, but against power that had grown distant and deaf.

That instinct has always lived comfortably in the Island City.

From Conchs who survived by the sea to smugglers who lived by their wits, the Southernmost City has long been shaped by self-reliance and skepticism of distant authority. Federal power arrived late, heavy, and often confused by the terrain. The farther away decisions were made, the less sense they made on the docks and streets where consequences landed. That skepticism was not lawlessness. It was colonial memory.

Which is why the Conch Republic still matters.

Its mock secession was parody with teeth — born of perceived punishment. When federal roadblocks throttled traffic at the top of the Keys, strangled tourism, and subjected residents to intrusive scrutiny, the Island City responded the way colonies always have when distance replaces dialogue. The official rationale was enforcement. The island’s reading was colder.

That not enough of what Washington wanted was moving north. That not enough of what it counted on was moving south. Whether fair or not, the belief took hold because the capital was far away and uninterested in explanation. Legitimacy collapsed on contact with the island.

When protest is ignored long enough, it turns sarcastic, and when sarcasm keeps landing, it eventually hardens into something political whether anyone plans it or not.

The founders understood this pattern intimately. Tea was never the point. Distance was.

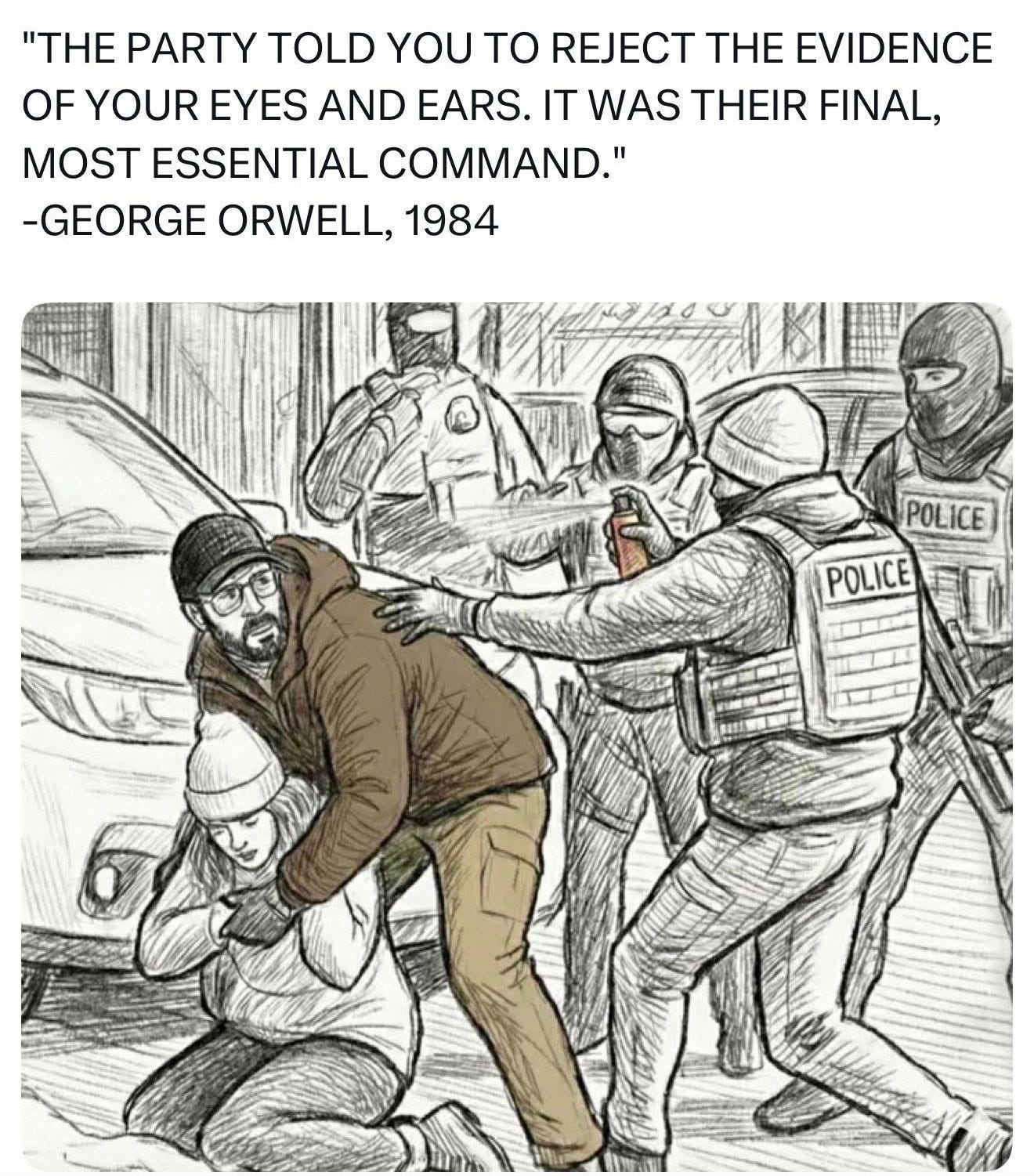

What they did not imagine was a permanent, militarized domestic enforcement state. They never pictured armed federal agents moving through civilian neighborhoods with the posture of soldiers rather than public servants. They did not imagine local law enforcement inheriting military hardware through surplus pipelines. They did not imagine enforcement that felt less like governance and more like occupation.

Yet that is the atmosphere taking shape.

As TPS protections expire, federal enforcement looms larger in daily life in the Southernmost City. Armored vehicles. Tactical boats. Masked operations. Surveillance tools once reserved for foreign theaters. Each step justified as reasonable. Each escalation incremental. Each tool framed as necessary.

Until the question becomes unavoidable.

What is next?

Persistent aerial surveillance? Force applied remotely, without familiarity or proximity? Enforcement without accountability? These are not speculative fears. They are existing capabilities awaiting normalization.

The founders feared mobs — but not only the kind carrying torches. They feared state power that behaves like a mob while cloaked in law. Groups enforcing distant commands, insulated from local accountability, diffused of responsibility, moving through communities as an occupying presence rather than a civic one.

In the 18th century, those men wore red coats.

In the 20th century, Europe learned a harder lesson. They wore arm bands.

Internal security forces in Nazi Germany did not begin as death squads. They began as enforcers. Immigration police. Internal monitors. Loyalty-checkers. Bureaucrats with guns. Over time, the distinction between enforcement and terror disappeared — not because every individual was evil, but because the system was designed to answer upward, not locally. That force had a name: the SS.

The comparison is not about ideology. It is about structure.

When modern agencies such as the Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement operate masked, heavily armed, far from borders, insulated from community oversight, and accountable only to a distant capital, the distinction between law enforcement and coercive force collapses in the public mind. Not because every agent is corrupt. But because systems matter more than intentions.

This is how republics sleepwalk.

As one bitter, postwar refrain would later ask: “If there was just some way we could have seen this coming.”

History answers back, quietly and relentlessly: there always was.

Meanwhile, Americans live with a reality the founders never did: mass shootings as recurring trauma. Children sheltering under desks. Classrooms turned into killing fields. Soldiers attacked by fellow citizens. These horrors have reshaped the national conscience and complicated any honest discussion of arms.

And yet, the loudest defenders of the Second Amendment insist it exists to protect citizens from government tyranny. If that is true, the comparison sharpens.

Tyranny does not announce itself wearing a crown. It returns in patterns: distance, loyalty over law, force replacing consent, leaders who personalize power and treat dissent as disorder.

Today, the ocean separating ruler from ruled is gone. The distance is political. It is Washington, D.C. via Tallahassee.

And in that distant capital, the country is confronting an embryo the founders would have recognized instantly.

That embryo has a name: Donald Trump.

None of this requires foresight — only the uncomfortable act of noticing how these things have unfolded before. Like the Mad King, Trump demands loyalty over law, frames enforcement as strength, treats dissent as betrayal, and mistakes volume for legitimacy. King George III believed he was restoring order, too. So did King Louis XVI.

Which raises a final, uncomfortable question.

If Temporary Protected Status had existed in the era of Alexander Hamilton — if a distant capital had abruptly stripped lawful residents of protection and unleashed enforcement into civilian life — what would Hamilton have done?

He would not have cheered it. Hamilton believed fiercely in national authority, but just as fiercely in law, due process, and restraint. He warned that legitimacy collapses when power outruns consent. He built institutions precisely to prevent arbitrary rule.

History offers a cruel irony. Hamilton did not die at the hands of a tyrant. He died because politics curdled into personal power, because systems failed and disputes escaped the law — at the hand of Aaron Burr.

That is the lesson, not the punchline.

When disputes meant for courts, legislatures, and public argument are settled by force, everyone loses — even the architects of the republic. The founders designed constitutional remedies precisely to avoid that end.

So the answer is not violence.

Hamilton would have fought in print. In law. In institutions. In public argument. And he would have warned — loudly — that stripping protections, expanding enforcement, and normalizing force from a distant capital is how republics drift toward the very chaos they claim to prevent.

The Second Amendment was written as a warning, not a fetish — a reminder to mad kings, crowned, bureaucratic, or personalized, that power flows upward, not down.

The American Revolution began over tea.

The temperature has already dropped; pretending otherwise is the luxury of people not standing outside.

And reckoning follows when distant capitals forget who they serve.