As TPS Deadline Nears, ICE Facial Recognition Use — Including on Children — Raises Alarm in Key West

With Haitian protections set to expire Feb. 3, expanded use of a mobile facial-recognition app — and efforts to curb public warning tools — are heightening fear across the Florida Keys.

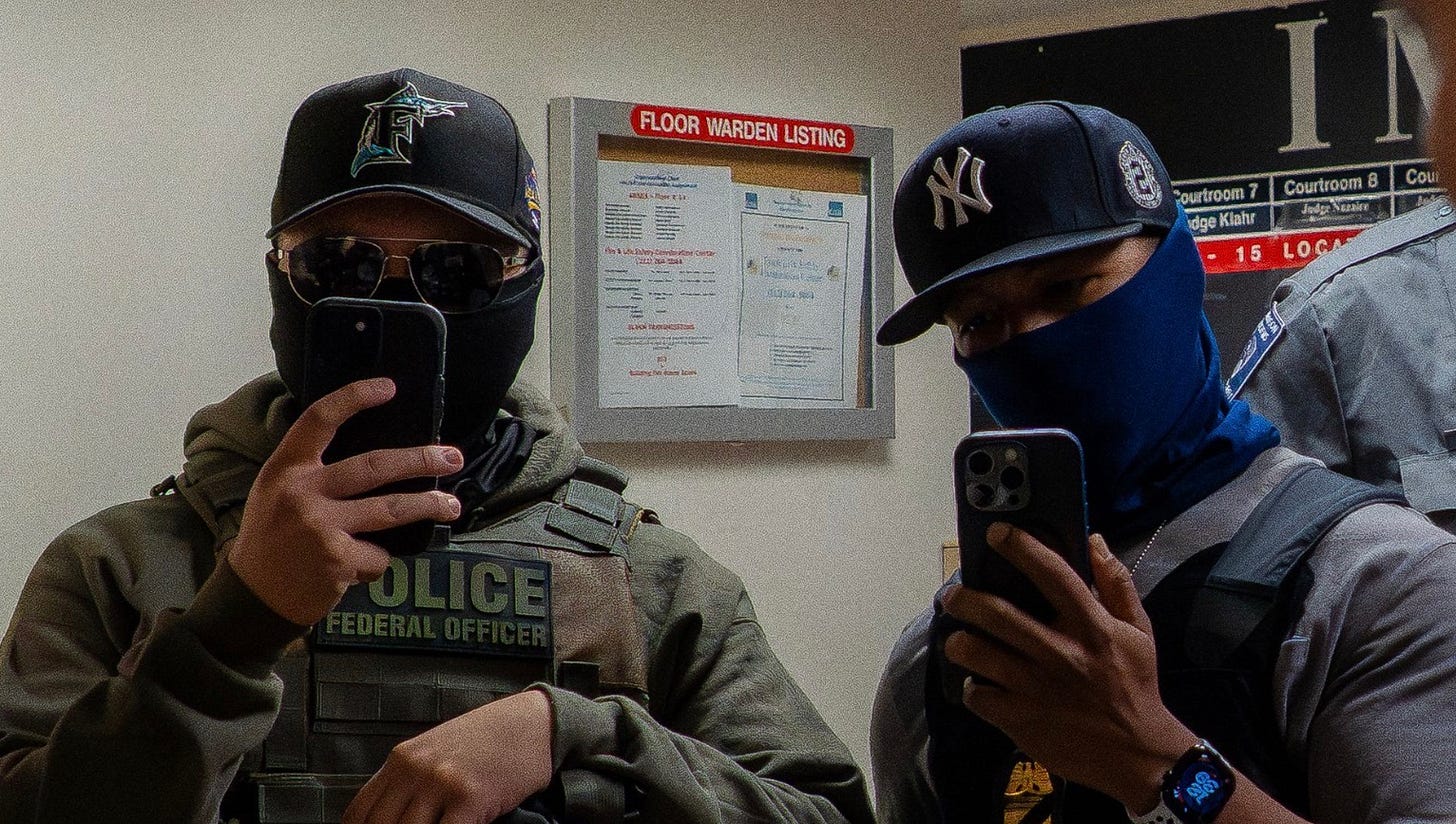

As the Feb. 3 deadline for the expiration of Temporary Protected Status for Haitians approaches, anxiety is rising in Key West’s immigrant community amid mounting evidence that Immigration and Customs Enforcement is expanding the use of mobile facial-recognition technology — including in street encounters involving U.S. citizens and minors — while the Trump administration simultaneously presses tech platforms to limit public tools that warn of enforcement activity.

At the center of the controversy is Mobile Fortify, a smartphone application used by federal immigration agents to photograph faces and scan fingerprints in the field, instantly comparing that biometric data against multiple federal databases. According to court filings, civil liberties advocates and investigative reporting, some of those databases have previously been deemed too unreliable for use in arrest warrants.

The Department of Homeland Security has acknowledged that Mobile Fortify has been used more than 100,000 times nationwide. That figure is cited in a lawsuit filed earlier this month by the State of Illinois and the City of Chicago, which accuses DHS, ICE, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and senior Trump administration officials of operating an unlawful interior enforcement regime built around coercive stops and routine biometric scanning.

One incident described in the lawsuit has become emblematic of the broader shift now under legal scrutiny.

According to the complaint, masked federal agents stopped two teenagers riding bicycles near an Illinois high school last fall and demanded proof of citizenship. One teen, who said he was 16 and a U.S. citizen, told agents he had a school ID but did not have it with him. An agent then asked another, “Can you do facial?” A cell phone was pointed at the teenager’s face, appearing to capture his image.

The moment, described through sworn allegations rather than body-camera footage, illustrates how facial recognition has moved beyond ports of entry and investigations into everyday encounters — including with children far from the border.

The lawsuit alleges DHS agents have used facial recognition on minors who are U.S. citizens without consent, individualized suspicion, or meaningful public limits on data retention and sharing. It further claims biometric data collected through Mobile Fortify may be retained for up to 15 years, regardless of citizenship or age, potentially creating long-term biometric records for children never charged with a crime.

Mobile Fortify was first revealed last summer by 404 Media through leaked internal emails. Subsequent reporting cited DHS documents stating individuals cannot refuse to be scanned. The outlet reported the app draws from multiple systems, including CBP’s Traveler Verification Service, Border Patrol databases, and the Office of Biometric Identity Management’s Automated Biometric Identification System, which together comprise an estimated 200 million images.

Legal experts say the technology’s real-time use in street encounters sharply increases the risk of misidentification.

“Here we have ICE using this technology in exactly the confluence of conditions that lead to the highest false match rates,” said Nathan Freed Wessler, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s speech, privacy and technology project. “A false result from this technology can turn somebody’s life totally upside down.”

The Electronic Frontier Foundation — along with several other human rights groups wrote:

ICE’s reckless field practices compound the harm done by its use of facial recognition. ICE does not allow people to opt-out of being scanned, and ICE agents apparently have the discretion to use a facial recognition match as a definitive determination of a person’s immigration status even in the face of contrary evidence. Using face identification as a definitive determination of immigration status is immensely disturbing, and ICE’s cavalier use of facial recognition will undoubtedly lead to wrongful detentions, deportations, or worse. Indeed, there is already at least one reported incident of ICE mistakenly determining a U.S. citizen “could be deported based on biometric confirmation of his identity.”

Wessler warned the broader implications extend well beyond immigration enforcement. “ICE is effectively trying to create a biometric checkpoint society,” he said.

Those concerns are amplified by longstanding evidence that facial-recognition systems are less accurate when identifying women and people of color. In fast-moving encounters — poor lighting, partial facial views, stress, or individuals turning away — error rates increase further. 404 Media reported earlier this month that Mobile Fortify misidentified a woman during an immigration raid, producing two different incorrect names.

Critics say ICE often treats biometric results as definitive, even when other documentation contradicts them, and that agents are not required to conduct additional vetting before acting on a scan.

“Facial recognition — to the extent it should be used at all — is really supposed to be a starting point,” said Jake Laperruque, deputy director of the Center for Democracy and Technology’s security and surveillance project. “If you treat this as an endpoint, you’re going to have errors, and you’re going to end up arresting and jailing people that are not actually who the machine says it is.”

At the same time Mobile Fortify’s use has expanded, the Trump administration has asked Apple and other app platforms to remove or restrict applications that alert the public to ICE enforcement activity, according to civil liberties groups and technology watchdogs. Critics argue the combined effect narrows public awareness while dramatically expanding government surveillance capacity.

The legal challenge also highlights internal DHS policy contradictions. In September 2023, DHS issued Directive 026-11, acknowledging facial recognition as inherently privacy-sensitive, identifying age as a protected characteristic, and explicitly stating such technology “may not be used as the sole basis for law or civil enforcement actions.” The directive required human review of matches and emphasized transparency and accountability.

The lawsuit alleges the directive was rescinded on or before Feb. 14, 2025, shortly after President Donald Trump took office. The Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board later reported it could not confirm whether the directive remained in force, recommending DHS publicly clarify or reissue binding safeguards.

DHS has defended Mobile Fortify, saying it operates with a high matching threshold, queries only limited immigration datasets, and does not scrape social media or rely on open-source data. A department spokesperson said the app is lawfully used nationwide and has not been curtailed by the courts.

Democratic lawmakers remain unconvinced. Legislation introduced Jan. 15 would bar DHS from using Mobile Fortify or similar tools outside ports of entry. In earlier correspondence, senators warned that “even when accurate, this type of on-demand surveillance threatens the privacy and free speech rights of everyone in the United States.”

In Key West, those national developments collide with local realities.

Haitians and other immigrants form the backbone of the Island City’s hospitality, health care, construction, and maritime workforce. Community leaders say the convergence of expiring TPS protections, expanding biometric enforcement, and the rollback of public warning tools has created deep uncertainty — particularly for families with children who may now face enforcement encounters carrying long-term consequences.

For many in the Florida Keys, the fear is no longer abstract. As enforcement technologies move from borders to neighborhoods — and from adults to minors — everyday moments near schools, workplaces, and sidewalks are increasingly viewed through the lens of potential biometric capture, with impacts that may follow children and families for years.

ED. NOTE: Additional reporting and documentation from technology and civil-liberties publications contributed to this story.